Entre el protagonismo del narrador que centra la trama en su propia experiencia y la invisibilidad y omnipresencia de quien se sitúa fuera de la acción, la narración en segunda persona permite sublimar lo íntimo, aflorar la introspección, confesar. Decir aquello que a nadie más se diría. Sólo a ese “otro” a quien va dirigida la palabra. Ese “tú” que en ocasiones se presta también a la duplicación del sujeto narrativo. Un desdoblamiento, un mirarse en el espejo.

In contrast to the central role occupied by a narrator who focuses the storyline on firsthand experience, and the transparent and omniscient perspective of one placed altogether outside the action, second-person narrative creates the right environment for the sublimation of the inner forum, for introspection to flourish, for a confession to ensue; for the utterance of that which no one else should be able to hear—no one but the “other” to whom the words are spoken. That “you” which at times also doubles up as narrator. A disseverance, a looking at yourself in the mirror.

Desde 1981, treinta y cinco años antes de que surgiera, con el impulso y la venia de las redes sociales, lo que Joan Fontcuberta teorizó como “reflectogramas”, que eran los retratos en el espejo, usualmente eróticos, había un fotógrafo que desde los ochenta trabajaba ese retrato en el espejo, con una retórica todavía más compleja que la del autorretrato especular popularizado en internet. Este autor era Vasco Szinetar.

Long before the emergence (35 years, since 1981), with the endorsement and approval of social media, of what Joan Fontcuberta has called “reflectograms”—portraits taken before the mirror, most commonly in bathrooms or bedrooms and usually erotic in nature—there was a photographer who from the early 1980s was making portraits in front of the mirror, using an even more complex rhetoric than that of the specular self-portrait popularized by the Internet. This autor was Vasco Szinetar.

Con Venezuela como sede principal, Szinetar se dedicó a retratar a artistas y creadores alejado del tradicional discurso de la tercera persona que se ha mantenido en este género fotográfico desde sus inicios. Szinetar eligió la mirada susurrante de la segunda persona para mostrar ese diálogo entre él, fotógrafo, y su retratado. Lo hizo en una doble vertiente. Por una parte, eligió los servicios de hoteles, casas, despachos, donde encontrar un espejo y allí hacía la fotografía que, más que un retrato, era una narración con dos tramas. La del fotógrafo y la de su acompañante, desubicado por la originalidad.

In Venezuela, Szinetar captured artists and creators, distancing himself from the third-person discourse that has characterized photography since its origins. Szinetar chose instead to use the discreet look of the second person in order to show the dialogue between himself, the photographer, and his subject. He used a two-pronged approach. On the one hand he made use of hotels, homes, offices, anywhere he could find a mirror, and he would take his shot there, which more than a portrait would result in a narrative with two storylines: the photographer’s, and that of his companion, somewhat disconcerted by the originality of the concept.

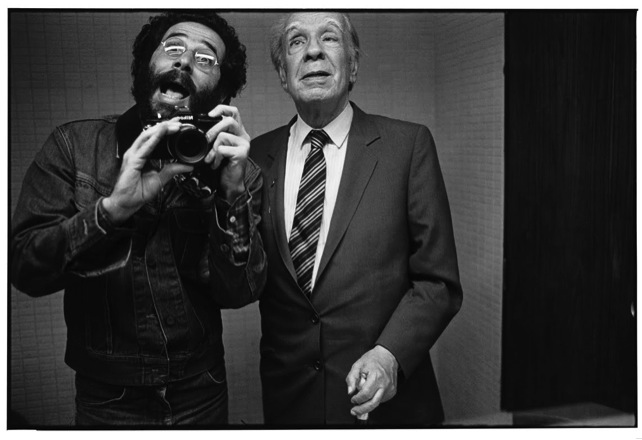

Jorge Luis Borges, 1985. Fotografía de Vasco Szinetar

Al igual que en los reflectogramas que surgieron más de dos décadas después, quien acciona la cámara se desnuda. En el caso de Szinetar, no de manera literal. No insinúa ni muestra la piel. Es aún más profunda, y por eso la segunda persona funciona con la eficacia literaria: su desvelamiento es intelectual, y surge por confesión: a quién admira, con qué alegría lo captura para su propia biografía. Borges, Rushdie, García Márquez, Vila-Matas… Además, algunos de estos retratos capturan el rictus más espontáneo de estos intelectuales, acostumbrados a la pose pero no a la locura contagiosa de su interlocutor.

Just as is the case with the reflectograms which would come to the fore over two decades later, the person operating the camera stands naked before it. In Szinetar’s case not quite literally. He shows no skin, nor does he insinuate he might. His nakedness refers to something deeper, which is why the second person works with literary efficiency: his undressing is intellectual and is triggered by a confession— the joy he feels when he finds the people he admires, and is able to add their portraits to his own biography. Borges, Rushdie, García Márquez, Vila-Matas… In addition to this, some of these images actually manage to capture the most spontaneous vein of these intellectuals, all too used to posing for a shot but caught off guard by the contagious madness of their interlocutor.

Nosotros, el público que observa la obra de Vasco Szinetar, nos entrometemos por esta magia surgida de una perspectiva bien elegida, entre dos personas que parecen no querer testigos. Y sin embargo, ahí estamos, escuchando el murmullo que surge de esa mirada. En Caña de Azúcar reunimos a 101 creadores que aceptaron el juego.

We, the audience looking at Szinetar’s work, meddle through the workings of a felicitous perspective in the affairs of two people who seem to long for no witnesses. And yet there we are, eavesdropping on the whisper that results precisely from that very look. In Caña de Azúcar we bring together 101 creators that accepted play the game.

Créditos / Credits

Autor / Author: Vasco Szinetar

Comisario / curator: Doménico Chiappe

Producción / Production: DayLight Lab

Coordinación / Coordinator: Gabriel Osío y Caña de Azúcar

© imágenes / Images: Vasco Szinetar

© Texto / Text: Doménico Chiappe

2differently

2abounds

best online paper writers

pay someone to write your paper https://term-paper-help.org/

write my apa paper

write my persuasive paper https://sociologypapershelp.com/

pay to do paper

buy a college paper https://uktermpaperwriters.com/

pay to write paper

paper writer https://paperwritinghq.com/

pay people to write papers

write my nursing paper https://writepapersformoney.com/

write my paper college

buy papers online for college https://write-my-paper-for-me.org/

write my paper canada

pay someone to write a paper for me https://doyourpapersonline.com/

ghost writer for college papers

custom papers for college https://top100custompapernapkins.com/

help writing papers for college

can you write my paper for me https://researchpaperswriting.org/

write my math paper

college paper writing services https://cheapcustompaper.org/

need someone to write my paper for me

paper writing website https://writingpaperservice.net/

custom written college papers

buy cheap paper https://buyessaypaperz.com/

college paper writing services

help writing a college paper https://mypaperwritinghelp.com/

do my papers

academic paper writing services https://writemypaperquick.com/

help write my paper

custom college paper https://essaybuypaper.com/

write my sociology paper

where to buy college papers https://papercranewritingservices.com/

buy papers online

best write my paper website https://premiumpapershelp.com/

do my college paper

psychology paper writing service https://ypaywallpapers.com/

paper writing services legitimate

buying papers online https://studentpaperhelp.com/